While much of the Western discourse about Ukraine places the recent developments in the context of a Russia-EU-West framework, an analytical perspective from within Ukraine has been largely missing.

Ukraine has been thrown into an extremely precarious situation after three months of protests (Euromaidan) which culminated in violence and up to 100 deaths, the impeachment of President Viktor Yanukovych, the disintegration of his government, the forming of a new temporary government, the announcement of presidential elections to be held on 25 May, and the release of jailed ex-Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko.

Truly unprecedented scenes of violence and political change took place in Kiev within a matter of a few days, leaving little time to make sense of it all. What at first sight seems like a triumph of the people over a corrupt government might just be a Ukrainian Trojan horse allowing for the reentry of discredited and bitter politicians, including Tymoshenko herself, to the political arena.

Ukraine faces three immediate and rather serious issues. First, it needs to have a functional government. The political infighting and jockeying for power that is already occurring needs to be adequately subdued in order to provide the country with functioning state organs and institutions. By the looks of the proposed candidates though, it seems that it will be a choice between politicians from the Yuschenko era, or popular personages from Euromaidan (meaning literally “Eurosquare” in Ukrainian) with no real political experience. Second, the economy desperately needs to be stabilized. With the Ukrainian Gryvna falling daily against the Dollar and the Euro there is a real chance of another economic crisis like the one in 2008 when the Gryvna/Dollar ratio fell from less than 5:1 to nearly 10:1 before stabilizing at 8:1. The rate is currently more than 9:1.

Third, the central government needs to find a way to (re)integrate the regions. Euromaidan protests of various sizes broke out all around the country where many local and regional administrations, police stations, and military bases in western and central areas falling into the hands of the protesters. Conversely, now that Yanukovych has been removed, eastern and southern regions refuse to recognize the current temporary government and there is a fear that Crimea might go to Russia, either willingly or forcefully. What Ukraine needs is a non-polarizing and non-antagonistic leadership, something that seemed unlikely even before Tymoshenko was released from prison.

Tymoshenko is a very divisive figure within Ukrainian politics. She amassed her fortunes in the natural gas business during the 1990s in her native Dnepropetrovsk on the back of then-regional governor and later Prime Minister Pavel Lazarenko (who later was sentenced to nine years in US Federal prison for money laundering). After changing sides numerous times she ended up with Viktor Yuschenko and took part in the Orange Revolution in 2004, passing herself off as a Ukrainian-speaking nationalist with the help of language tutors and an image consultant. Even if many Ukrainians do not know or remember these events, most of them surely remember her time as the Prime Minister. Her bitter quarrels and tugs of war with President Yuschenko brought the government to a standstill and played a large role later in her losing the 2010 presidential elections to Yanukovych. While the actual charges brought against Tymoshenko as well as the timing of her imprisonment may have been intended as an act of political revenge, many Ukrainians felt she deserved to be in jail. Consequently, through its vocal support of Tymoshenko the West has legitimized a politician who has discredited herself on numerous occasions in the eyes of many Ukrainians, not least when she turned up on the Maidan stage in a wheelchair, began crying theatrically, and immediately placed herself at the front of a struggle she played no physical role in.

Despite being one of the main demands of Euromaidan, new elections might not determine very much. Elections in Ukraine are more about which group gets the power and access to state resources than which political party will do the most to improve the country. On the one hand Yanukovych and his government are gone, something the majority of Ukrainians are happy about. The problem now is Tymoshenko, who announced her intention to run for presidency. Will so many voters be turned off by her that they are willing to vote for someone like Sergey Tigipko representing Party of Regions? Such a turnaround happened in 2010 when Ukrainians willingly elected Yanukovych, the man they came to the streets to prevent from taking power in 2004.

Then there is Vitaliy Klitschko, notable for his near disappearance since the end of the violence. As the most active leader of the opposition troika, he gained certain respect despite the fact he is not an experienced politician. Much also depends on the reinstatement of the 2004 constitutional amendments and new parliamentary elections. As the parliament is strengthened at the expense of the presidency, the elections on 25 May will become less important in the long run. It remains to be seen if anyone can break the cycle and forge a new way forward.

A telling quote from a recent article in Ukrainskaya Pravda brings up a poignant reality when talking about the inability of any elites to replace this corrupt patronage system of relations as the Donetsk group has been replaced with ‘dear friends’ who are ‘obviously hungry and in the mood for revenge.’ Many of them are the same people who divided up the state’s resources during Tymoshenko’s previous time in office. They are no different than the Donetsk group who were just kicked out, they were ‘just better at concealing themselves, as they went around wearing vyshivanki’ (traditional Ukrainian embroidered shirts).

Patronage networks, clients, and oligarchs are features of many post-Soviet political systems. In Ukraine, however, certain groups have managed to adopt the façade of nationalism and democracy, fooling the electorate (and the West), while enriching themselves as much as possible before their eventual replacement by a rival network in the next election. This system did not originate with Yanukovych, and it looks like it will not end with him either.

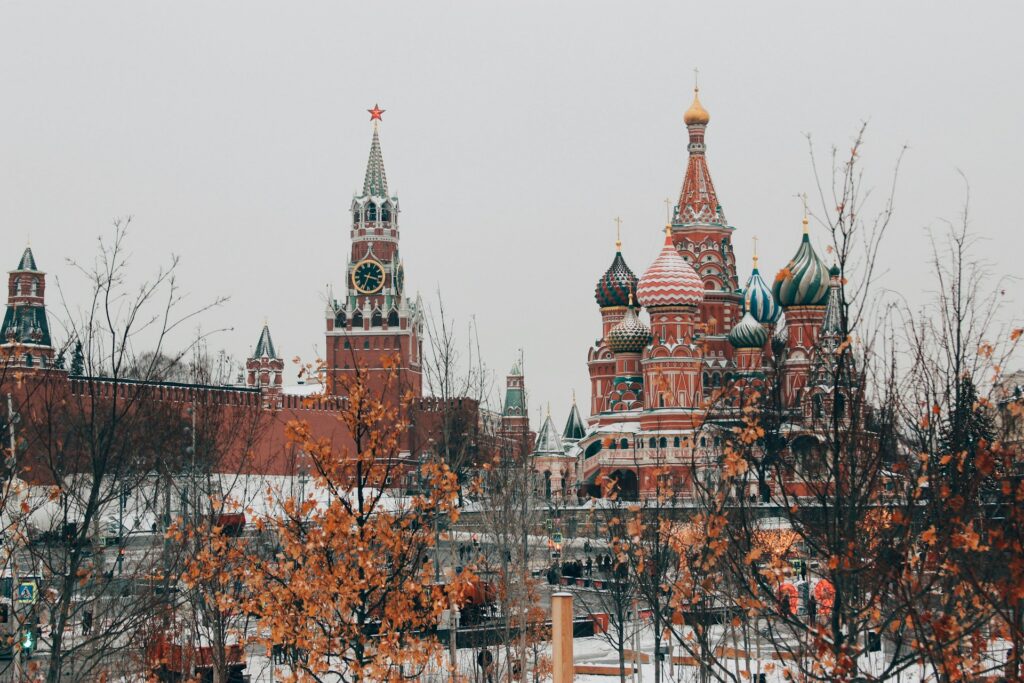

Article image: jorono / Pixabay