Last autumn’s war in Nagorno-Karabakh broke the status quo, which had roughly prevailed in the region since 1994. It claimed the lives of at least 6,300 military personnel and 200–300 civilians. While the ceasefire negotiated by the Russian foreign ministry and President Putin personally finally stopped this war, it also gave Russia an opportunity to assemble a few important pieces in its geopolitical puzzle in the wider South Caucasus region.

Arayik Haroutyunyan, the president of the self-proclaimed Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) Republic, had a grim announcement to make on November 10, 2020. Although the Armenian media had persistently reported about military achievements on the Armenian side of the war that had erupted on September 27, the war was ending with defeat and loss of territory.

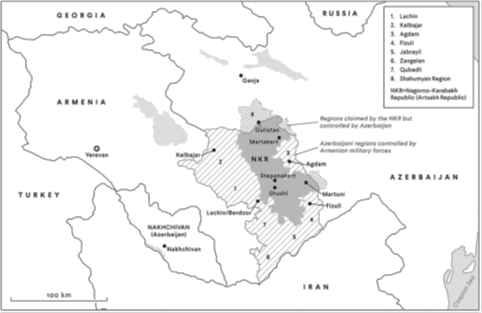

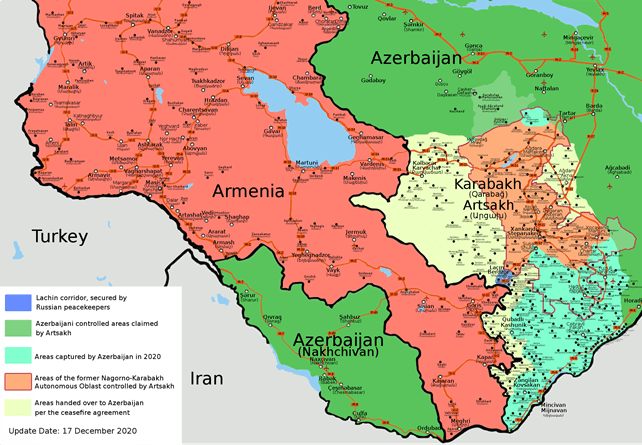

Four regions in the south, which had formed parts of the Armenian “security zone” around Karabakh since the 1992–94 war, were retaken by Azerbaijan. Additionally, almost the entire Hadrut region and certain areas of two more regions inside the Soviet-time administrative borders of Nagorno-Karabakh were under the control of the Azerbaijani forces. Moreover, they had taken over the historic fortress town of Shushi (Shusha in Azeri), which president Ilham Aliyev days before had declared to be an important symbol of Azerbaijan’s victory.

Peace Deal Brokered by Russia

Once the Azerbaijani flag flew over the mountainside town of Shushi/a, a peace deal brokered by Russia was concluded by the Armenian prime minister and the presidents of Azerbaijan and Russia. A trilateral statement signed on the night of November 9–10* froze the military positions of the warring parties to a new Line of Contact agreed to be controlled by Russia’s peacekeeping forces. A ceasefire was firmly established after three failed attempts, and this was done before the Azerbaijani forces were able to advance a few kilometres down towards Stepanakert, the administrative centre of the Artsakh Republic, where half of its population of 140,000 people lives.

A ceasefire was necessary to prevent a grave humanitarian catastrophe, but this was not the only reason why the war stopped on the southern outskirts of Stepanakert.

It was necessary to prevent a grave humanitarian catastrophe, but this was not the only reason why the war stopped on the southern outskirts of Stepanakert. The city, which has a Soviet-built, presently modernized airport, became the command headquarters of the almost two thousand Russian peacekeepers (contract servicemen with peacekeeping training), who were on their way to Karabakh before the ink was dry on the trilateral statement. Their mission will expand the military infrastructure which Russia already maintains in the region within the context of its military alliance relationship with Armenia.

The Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, who rose to power with Armenia’s “Velvet Revolution” in 2018, had no other option but to accept the peace deal. This war was different from the previous wars in that Azerbaijan was able to rely on Turkey’s military-technical support, and yet—contrarily to the expectations of many Armenians—Russia showed no signs of intervening in Armenia’s favour.

The involvement of Turkey in the conflict intensified Armenia’s mobilization for the defence of Artsakh, but the concept for the interlinked security of Artsakh and Armenia did not gain Russia’s support in the context of its alliance treaties with Armenia. Moscow argued that the war did not seriously threaten the territory of Armenia. The threat was not about an all-out invasion, although border areas in both Armenia and Azerbaijan were not spared by the war.

Armenia did not gain Russia’s support in the context of its alliance treaties with Armenia. Moscow argued that the war did not seriously threaten the territory of Armenia.

The trilateral statement signed on the night of November 9–10 allows Azerbaijan to regain all seven regions in the Armenian “security zone” around Karabakh. In addition, the Karabakh area subject to future negotiations will diminish by almost one third. The land connection to Armenia through Lachin will remain open under the control of the Russian peacekeepers.

However, the most complex issue is the realization of the corridor which the peace deal promises to create through Armenia’s Meghri region in the proximity of Armenia’s border with Iran. In addition to providing Azerbaijan a land connection to its exclave Nakhchivan, this corridor will provide Turkey a connection to Azerbaijan’s ports on the Caspian Sea and, consequently, connect it with important energy and trading routes in Central Asia and in China.

The most complex issue is the realization of the corridor which the peace deal promises to create through Armenia’s Meghri region in the proximity of Armenia’s border with Iran.

In Armenia, the corridor is a politically explosive issue. The people in Armenia were left disappointed by the results of the meeting between the Russian and Azerbaijani presidents and the Armenian prime minister in Moscow on January 11, 2021. The second trilateral statement signed then side-lined burning issues about border demarcation and prisoners of war and focused exclusively on transit issues and the construction of new road and railroad connections.

As in the Soviet past, large infrastructure projects were given top priority, although many local communities could not be informed whether they were on the Armenian or the Azerbaijani side of the border.

Tragic Nature of the Conflict

The peace deal made Pashinyan a “traitor” in the eyes of those Armenians, who presently pin their hopes on the possibility of a new, partisan war. However, many Armenians also question the necessity of having had the war continue for almost six weeks. They remind their fellow Armenians that it—for several years now—has been only a matter of time before Armenia would have to give up at least the seven regions.

The war did not cease, because nationalist ideology nourishes political power in both countries and makes it difficult to seriously negotiate with the “enemy”. Pashinyan could not make “concessions” without losing his political power; Aliyev had to win in order to secure his own power base. The brutal battle in the southern part of the disputed region and over Shushi/a clearly revealed the tragic nature of this conflict, which in both countries is a consequence of the dominant discourse, where the Karabakh issue is not only about the disputed geographical region but also about national identity and independent statehood.

The war did not cease, because nationalist ideology nourishes political power in both countries and makes it difficult to seriously negotiate with the “enemy”.

However, although the interplay of popular sentiment, elite structures, and political leadership is important in understanding the violent outbursts of the conflict, it does not suffice to make sense of its larger structure which also involves external interests. It gives us only a few pieces in its geopolitical puzzle.

If we examine the puzzle pieces in the game which Moscow plays to settle the conflict, we can see that the ideal combinations of action and policies (sets of joining pieces) are those which enable the development of Russia’s close relations with both Armenia and Azerbaijan and also facilitate its cooperation with Turkey and Iran. This puzzle is too complicated to be considered a premeditated plan.

It is more accurate to regard it as an ever-present game in which the pieces can be assembled at a moment when they fit together and help to strengthen the “stability and peace” that Russia pursues in and around Nagorno-Karabakh, in order to secure its long-term security interests and economic goals in the region.

War as an Opportunity to Put Pieces Together

The forty-four-day war put a strain on Russian diplomacy and policymaking, but it also gave Moscow an opportune moment to piece together a few components in its policy on the Karabakh conflict and the region around it.

First, the acknowledgement of Azerbaijan’s territorial gains in the peace deal promotes the positive relationship with Baku which Moscow needs to be able to further develop cooperation based on the strategic partnership between the two countries. Russia’s goal is to keep Azerbaijan committed to the bilateral treaty obligations which maintain friendly relations with Russia and provide a political framework for military-technical cooperation (the export of Russian arms and arm systems to Azerbaijan), energy trading and transport infrastructure development together with Russia.

Although the Minsk Group co-chairs (Russia, France and USA) had greeted Armenia’s “Velvet Revolution” as a new possibility for sustained negotiations, Prime Minister Pashinyan had avoided discussing the territorial issues and argued instead that Artsakh must speak with its own voice in the negotiations. When the war had achieved what the derailed negotiations could not achieve, President Vladimir Putin and other authorities in Russia did not forget to mention that a similar outcome could have been reached through peaceful means.

Russia’s goal is to keep Azerbaijan committed to the bilateral treaty obligations which maintain friendly relations with Russia and provide a political framework for the export of Russian arms and arm systems to Azerbaijan, energy trading and transport infrastructure development together with Russia.

Second, the agreement reached by the Azerbaijani and Russian presidents and the Armenian prime minister on the night of November 9–10 made it possible for Russia to achieve a goal it could not achieve back in 1994, in other words to send its peacekeepers to the conflict zone. Whereas the so-called Grachev plan (according to Pavel Grachev, Russia’s Minister of Defence 1992–96) proposed to deploy Russian peacekeepers in the Kelbajar region in the Armenian “security zone”, the present deployment is in the centre of Karabakh.

The initial numbers of the military personnel, together with the hundreds of Russian civilian experts and officials, whose mission is humanitarian work, suggest that the interactions between Russia and the self-proclaimed state will increase radically. Before the war, these interactions were only modest and, even then, organized through Armenia. Consequently, Russia will not only establish military presence in Artsakh; it will also play a key role in the future development of this disputed region.

The trilateral statement of November 9–10 allows Russia to extend its control over border zones in both Karabakh and Armenia.

Third, the trilateral statement of November 9–10 allows Russia to extend its control over border zones in both Karabakh and Armenia. The new Line of Contact between Artsakh and Azerbaijan, as well as the five-kilometre-wide Lachin corridor, which provides the land connection between Artsakh and Armenia through the territory regained by Azerbaijan, will be controlled by Russia’s peacekeepers.

The southern corridor, which will be designed to facilitate Azerbaijani and Turkish transit through Armenian territory in the proximity of its border with Iran, will in turn be controlled by the Border Guard Service of Russia’s Federal Security Service. These arrangements in the proximity of the border with Iran, which traditionally is Russia’s strategic border, are flexible to accommodate changes as the situation evolves in a region which may well become a hotbed of conflict and tension.

Russia also places high strategic importance on the Armenian border with Turkey. Russia’s military presence is already secure on this border due to its major military base at Gyumri.

Regional Affairs Controlled by Regional Powers

Fourth, the war gave Russia an opportunity to argue that regional affairs can be best controlled by regional powers. Although it is persistent in its argument that the OSCE Minsk Group must remain the formal framework of negotiations, it keeps the Armenian part of Karabakh in its own control and develops practical cooperation with Turkey.

Russia’s interpretation of the memorandum on the establishment of a joint Russian–Turkish ceasefire control centre, which was signed by the Russian and Turkish ministers of defence, Sergei Shoigu and Hulusi Akar, on November 11 (2020), shows that the new Line of Contact is meant to be a dividing line between Russian and Turkish interests. The joint control centre will operate in Agdam on the Azerbaijani side of this line and use mainly drone technology for carrying out its monitoring tasks.

The possible presence of the Turkish military personnel in the area controlled by Artsakh is a highly contentious issue in Moscow’s relations with Ankara. The war revealed disagreement between the two parties on several issues starting from Turkey’s open support for the use of military force in the disputed region and its practices to recruit mercenary fighters from Syria for combat tasks there.

The war gave Russia an opportunity to argue that regional affairs can be best controlled by regional powers.

Yet their cooperation in the post-war situation prompted Russia’s foreign minister Sergey Lavrov to applaud this relationship between “independent states” which “do not put forward ultimatums” and “do not bow to anyone”. Instead, they can reconcile their differences and “combine efforts and promote a ceasefire in various conflict zones”. Lavrov’s argument suggests that Russia will seek to convert the challenges brought by Turkey’s increased military presence in the South Caucasus into new opportunities and strengths outside this region.

Iran is a far less problematic piece in Russia’s Karabakh puzzle. Iran’s main concern is the security and stability of its northwestern border regions on its borders with both Armenia and Azerbaijan. The war strengthened Tehran’s efforts to maintain good relations with both neighbouring countries and to promote the development of different forms of cooperation between the three large states—Russia, Turkey and Iran—and the states in the South Caucasus region.

The development of regional cooperation supports the idea of a regional context for the negotiations, which in turn expands Russia’s room for manoeuvre in its relations with the two other co-chairs in the Minsk Group. Consequently, Iran’s diplomatic activity has been welcome in Moscow: it supports Russia’s policies from the side-lines of the trilateral negotiations and helps constrain the ambitions of both Turkey and the Western states in the region.

Tightened Structure of the Conflict

Finally, the peace deal ensures that Karabakh continues to be Russia’s main leverage over the direction of security policies and international integration in both Armenia and Azerbaijan. Without Russia, Armenia will not be able to credibly resist Azerbaijan’s claims over the remaining areas of Karabakh. Similarly, without developing its partnership with Russia, Azerbaijan will lack the means to prevent Russia’s policies from weighing in favour of Armenia on the Karabakh issue.

Armenia and Azerbaijan would be able to disassemble the puzzle that Russia attempts to compose by dividing the disputed territory between the two of them peacefully. If political space for such initiatives did exist, the conflict would be very different to what we see today.

The 2020 war resulted in a smaller region where international status remains unsolved, but it also locked the conflict into an even tighter security structure than before the war. In consequence of the peace deal, the security arrangements for the self-proclaimed state of Artsakh have changed.

Armenia and Azerbaijan would be able to disassemble the puzzle that Russia attempts to compose by dividing the disputed territory between the two of them peacefully. If political space for such initiatives did exist, the conflict would be very different to what we see today.

Before the war, Artsakh had to rely on the tenuous connection between the Armenian policy, which states that Armenia is the guarantor for its security, and Armenia’s alliance relationship with Russia. After the war, the people living in Artsakh can reasonably expect that the Azerbaijani and Turkish military personnel will be aware of the risks involved in incidents that endanger Russia’s peacekeepers.

They can point out that the military and political elites in the respective hostile countries should recall the events in neighbouring Georgia. In 2008, a deadly attack on Russia’s peacekeepers in South Ossetia became instrumental for Russia’s military intervention and the final separation of South Ossetia and Abkhazia from Georgia. After 2020, the people in Artsakh can argue that Russia’s peacekeeping in Karabakh is pre-emptive action intended to forestall a similar large-scale military conflict in this South Caucasus region.

From the perspective of Artsakh, the news announced by Haroutyunyan on November 10 was thus not entirely grim.

*) Because of the time difference the date of signing the statement in a video conference in Moscow is November 9, whereas the date in both Baku and Yerevan is November 10.

Helena Rytövuori-Apunen has retired from the University of Tampere, where she was a Senior Researcher at the Tampere Peace Research Institute and a Professor in Politics and International Relations. Her latest single-authored monograph is titled Power and Conflict in Russia’s Borderlands: The Post-Soviet Geopolitics of Dispute Resolution (I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury, 2020). The present article is a new, original text.

Pingback: About my work – Helena Rytövuori-Apunen