Indonesia has elected a new president and representative members to serve for the next five years. Issues of democratic regression have been discussed since 2020 and such practices along with nepotism were key issues in this important election.

On 14th of February 2024, Indonesia had an important election. In this complex election – that Reuters News called the “biggest single-day election” – more than 200 million voters elected the new president and vice president, and legislative members on three levels of the region (national, provincial, district/city) including a national “senator”. Voters used five ballot papers in different colors.

Indonesian election of 2024 was important as President Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, could not run again after completing two five-year terms as president. The election was big, involving over 200 million voters in 823 000 polling stations across the country – 12 million more voters than the previous 2019 election. The young voters were a significant voting cohort, 55% or around 114 million youths: the Millennial generation (born between 1980–1995), and Gen Z (1997–2006), with 33,6% and 22,85% respectively, dominated the voters. I am also one of 1,7 million voters abroad.

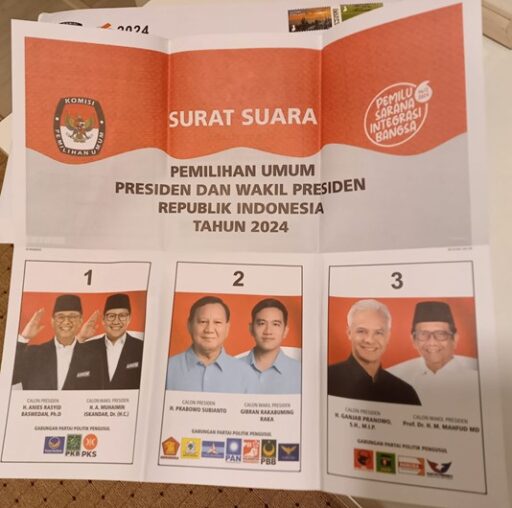

The election for president and vice-president received the most attention. There were three pairs of candidates for president and vice-president and they are given numbers as in ballot papers: number one: Anies Baswedan – Muhaimin Iskandar (supported by four political parties); number two: Prabowo Subianto – Gibran Rakabuming Raka (supported by five parties); and number three: Ganjar Pranowo – Mahfud MD (with the support of four political parties).

Both Anies Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo were governors previously, while Prabowo Subianto was ex-military general, the current Minister of Defense and Jokowi’s opponent in both 2014 and 2019 elections. Jokowi’s party is PDIP whose supported candidate nomination number three, Ganjar-Mahfud.

Jokowi’s victory in the 2019 election led to Prabowo joining his government and marked no opposition in the Indonesian executive branch, and ultimately showed democratic regression. Such democratic regression has been witnessed in Indonesian society. This is ironic, as President Jokowi Widodo who won in the direct presidential elections both in 2014 and 2019 against the New Order luminary Prabowo, was the one who brought it back. The authoritarian regime of 32 years, New Order, led by president Suharto was toppled in 1998, and voters elected Jokowi instead of Prabowo to avoid the existence of the old regime in the country.

According to the edited volume of the Democracy in Indonesia. From stagnation to regression? the signs of democratic decline were seen especially in Jokowi’s second term. There were “populist mobilizations, growing intolerance, and deepening sectarianism, increasingly dysfunctional electoral and representative institutions, the deterioration of civil liberties and the executive’s expansion of an authoritarian toolkit for suppressing opposition and curtailing criticism”. Moreover, there was no formal opposition to the government and nepotism became rampant, especially with the selection of Jokowi’s son as Prabowo’s vice president.

In early February, at least 30 universities expressed their concern towards the government, protesting the government’s partial support toward certain candidates and the election machine or institutions, allegedly leading to election fraud.

After the election, most quick count surveys predicted that Prabowo Subianto won the presidential election in the first round with 58% of votes. Prabowo’s winning was the culmination practice of such democratic regression. The election result was still shocking, despite the open fraud and unfair attempts of the president to make Prabowo win, as shown in the film Dirty Vote. Released a few days before the election, the film showed “the intricacies of the purported systemic, structured, and massive election fraud throughout the electoral process fabricated by the current president, Joko Widodo”.

The fraud did not only involve the institutions –The Constitutional Court or Mahkamah Konstitusi/MK; the Election Commissioner or Komisi Pemilihan Umum/KPU, and the election supervisory agency or Badan Pengawas Pemilu/Bawaslu. These institutions’ actions supported indirectly the presidential candidate number two, Prabowo-Gibran, it also involved village and community leaders and newly appointed regional leaders, mingled with money politics (spreading money to support certain candidates), strategic distribution of social assistance, and manipulation of the electoral mechanism.

The concern was voiced by the academic communities calling for electoral integrity and warning the government for weakening democracy. In early February, at least 30 universities expressed their concern towards the government, protesting the government’s partial support toward certain candidates and the election machine or institutions, allegedly leading to election fraud. Exactly what the documentary film Dirty Vote had shown.

Controversial candidates

Thanks to Jokowi’s support, Prabowo’s victory was unstoppable. His running mate was Jokowi’s elder son, 37-year old Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the Mayor of Solo city for two years. Gibran’s candidacy was initially hindered by the law (Law 7/2017 on regular election) that enacted the age of presidential candidate and vice president must be at least 40. Yet, the Constitutional Court—led by Jokowi’s in-law, Gibran’s uncle, Anwar Usman – opened the way for Gibran’s vice president candidacy by adding the phrase “experienced in regional heads” and the decision took immediate effect.

Even when the Ethical Council of the Constitutional Court decided that Anwar Usman was violating the code of ethics for judicial review (due to personal interest) and removed from his position, Gibran’s candidacy was still underway. Prabowo chose Gibran as his running mate, on the last day of election registration in late November 2023. The move was sudden, as Gibran was considered to lack experience as a mayor and especially as vice president. The skepticism about Gibran remained.

It was obvious that due to this controversial background, Jokowi would support his son running as vice-president. This meant that Jokowi also supported Prabowo to win in the 2024 election as president. Jokowi had attempted to lengthen his term to the third period, despite his saying otherwise. This was not possible according to the constitution, which limits the terms the president can serve to a maximum of two. He gave his support to a particular candidate but only hinted that the president could also do the campaign, according to the law on the election.

To soften his public image especially for young voters, Prabowo was rebranded as a cute and harmless grandpa, and in social media his picture where he was playing with cute cats was widely circulated.

This hint was misleading as the law enacted, that the president could only do the campaign if he is the incumbent running for the second term, or he is supported by his own political party. Jokowi as the president obviously could not run anymore, and he supported candidate number two, and not number three, as his political party, PDIP, supported.

Prabowo Subianto is another controversial figure. He was an ex-military general linked to the authoritarian regime led by president Suharto, by marriage to one of Suharto’s daughters. Prabowo was accused of human rights abuse during his military leadership in East Timor, and was banned from entering the United States until 2020. The ban was lifted when he became the Minister of Defense in Jokowi’s government. He was suspected of being responsible for student kidnapping and torture in 1997–98 leading to his being dismissed from the military. Unfortunately, since 2004, previous presidents in office were not interested in investigating the historical case of 1997–98 which toppled the authoritarian regime and included human rights abuses involving Prabowo.

Prabowo has been haunted by his past, in every election human rights issues have come up into public discussion. Prabowo has dodged the issue as part of the Indonesian democracy. The case was “resolved” when President Jokowi recently gave Prabowo a “four-star honorary general rank” which was condemned by human rights activists, including the families of the victims whose fate was unresolved because of Prabowo’s actions. Activists also saw this as “Jokowi’s attempt to accumulate power for him and his family”.

In the 2024 election, to “soften” his public image especially for young voters, Prabowo was rebranded as a cute and harmless grandpa, and in social media his picture where he was playing with cute cats was widely circulated. Gibran’s youth was also highlighted. Such advertisements were successful, although these controversial background promotions of the pair were seen as worrying.

Systemized election fraud?

President Jokowi is known to have popular support, roughly 80%, which made him the kingmaker. Therefore, whoever Jokowi supported was likely to succeed. Jokowi is from the PDIP party and therefore, at first hinted to support the presidential candidate Ganjar Pranowo, from the same PDIP party. In late 2022 he said to support the leader with “white hair”, which described Ganjar’s hair. But after his son’s candidacy, nepotism was clearly underway. Nepotism together with collusion and corruption was one of mandates for the Indonesian reform back in 1998, when the authoritarian regime was overthrown, but was brought back by Jokowi himself.

Not all controversies were with the candidates either. Also, the Constitutional Court or Mahkamah Konstitusi/MK with the Election Commissioner or Komisi Pemilihan Umum/KPU, were questioned for their integrity. The head of KPU committed the third ethical violation, surrounding Gibran’s vice presidential candidacy. The general election supervisory agency or Badan Pengawas Pemilu/Bawasluwas also alleged for not having “teeth” to question or impose sanctions towards many frauds practiced by KPU.

Quo vadis Indonesia’s democracy

With such a challenging background, people cast their votes. Indonesians are known to follow the rules, including participation in elections, thus the turnout vote was around 80%. Polling stations were opened from 7.00 to 13.00.

Abroad, the election was conducted on the previous weekend, but the count actually took place at the same time as in Indonesia, on election day, February 14th. People went to cast their votes enthusiastically and showed their purple finger as the sign of casting their votes. It was a national holiday too.

A few hours after the ballot stations were closed, and counting at the local stations closed, a quick count from a credible survey organization showed the expected election results. Usually the surveys are collected from around 2000–2500 stations with around 3% margin of error. In such a quick count, the general result was shown as the PDIP (Jokowi’s party), Golkar (old regime party) and Gerindra (Prabowo’s party) gained the most votes with approximately 16–17%, 14% and 13% vote shares, respectively. Other parties got less than 10% but as long as the support is higher than 4%, the parties earn seats at the national parliament. There were expected to be around eight political parties taking roles in parliament.

For the presidential election, due to Jokowi’s support, Prabowo swept the votes by more than half. The calculation showed Prabowo-Gibran 57–59%, Anies-Muhaimin 25% and Ganjar-Mahfud 16–17%. It was not surprising, with the many anomalies in vote counts, Prabowo gained more than 500 votes from one polling station, a suspected vote bubble, as one polling station usually only has around 300 votes. Jokowi’s supporters were considered likely to follow Jokowi and his hints to vote for Prabowo-Gibran. Prabowo and his team quickly celebrated their victory based on the quick counting results that evening.

The huge geographical coverage area means counting the votes takes time. The count was still done manually. A new recapitulation application, Sirekap, was introduced, but due to its difficulties in reading the numbers or uploading the info, the election result was based on manual counting.

While fraud and manipulation were suspected, as Jokowi ran many state policy support for Prabowo, people became aware of how the democratic regression was in place. The pre-election survey showed, that Prabowo electability was around 40%. Therefore, it was quite a shock to see Prabowo’s winning more than 50% of votes in one round. Indeed, to win outright and avoid a second-round runoff, the leading candidate needs more than 50% of total votes cast and at least 20% of the ballot in half of the country’s provinces.

Fraud charges concern changing of the results, and not the process of the election, which is hard to show beyond numbers.

In the formal election result on 20th of March 2024, Prabowo-Gibran won with 58,6% votes in 36 out of 38 provinces, followed by Anies-Muhaimin with 24,9% and Ganjar-Mahfud 16,5%. Eight political parties continue to be in the parliament, with PDIP – Jokowi and Ganjar’s political party – got the highest votes, 16,72%, followed by Golkar (15,29%) and Gerindra (13,22%). This was another unusual practice in Indonesian politics, that the winning party will not automatically lead the government, as the president is directly elected, and his/her personality matters for voters.

Jokowi’s government and his supporters called many times for “letting democracy work” or “letting people vote to elect their president”, as if electing president is only about vote share, and not also about the process. If the manipulation was systematic due to political actors, the institutions themselves, or the system, including intimidation, one would ask, how could the result be fair?

The losing candidates prepared their cases of fraud to be brought to the Constitutional Court. However, knowing that the Court was already in the grip of the incumbent president, any allegation of fraud is not likely to change the result of the election, especially the presidential election. Indeed, these fraud charges concern changing of the results, and not the process of the election, which is hard to show beyond numbers.

These events showed the fragility of Indonesian democracy, with political elites’ lack of political ethics, as shown in this year’s election.

There is another possible political way to proceed, that is establishing an Inquiry Committee (hak angket) at the parliament, Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat/DPR, to inquire the president, ministers and actors of institutions of the alleged fraud, so narratives and stories behind the scenes can be studied and analysed. This perhaps could be the way to re-establish a democracy process once again in Indonesia: a signal to the new president, that he cannot do things as he pleases, but only within the corridor of laws and the constitution.

Establishing a parliamentary committee of inquiry is not hard, all needed is at least signature from 25 members of parliament from different parliamentary groups to sign a document calling for such an investigation. However, knowing the political cartel in Indonesia and no opposition against the government in the parliament, it would be a challenge to establish a courageus will to question the president.

In the public sphere, people rally on the streets and academics continue to protest the democratic regression prior to the formal election result. Indonesian election credibility was also questioned by the United Nations Human Rights Committee (CCPR) concerning president Jokowi’s intervention. This directly affects the credibility of the new president.

These events showed the fragility of Indonesian democracy, with political elites’ lack of political ethics, as shown in this year’s election. Democratic regression and nepotism should be mitigated better in the future. The president should be impartial and not break the safeguards needed to protect Indonesian democracy now and in the future.

Ratih D. Adiputri is a postdoc researcher at the Department Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä, working for the project on United Nations and multilateralism, funded by the Kone Foundation.

Article image: Wisnu M. Adiputri: Ballot boxes in Jogjakarta, Indonesia