While Israel is using the contest to distract from its actions in Palestine, EBU is complicit in enabling Israel by insisting that the contest is non-political.

On 4th December 2025, after months of delays and uncertainty, fans of the Eurovision Song Contest received news many had hoped would not come. At its winter General Assembly in Geneva, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) cancelled a vote on Israel’s participation.

Israel, which the Palestinian Health Ministry in Gaza states has killed at least 70,000 Palestinians in its genocide against Palestine since October 2023, will be allowed to participate in the 2026 Eurovision in Vienna.

Israel’s determination to stay in Eurovision comes as little surprise to those who have followed the contest over recent years. President Isaac Herzog has intervened several times to ensure the state’s participation, most recently meeting with Roland Weissman, director of the Eurovision 2026 host broadcaster, Austria’s ÖRF, “to ensure Israel participates”, and creating a “dedicated team” for a concerted diplomatic campaign to keep Israel in the contest.

But the ultimate decision over whether Israel would be allowed to stay in the contest was made by the EBU. That decision raises important questions about the role the EBU plays in enabling states to use the contest for culturewashing, and what that means for audiences.

Culturewashing and complicity

A large body of scholarship on sport-, art-, culture- and pinkwashing shows us how states use the platforms provided by mega-events like Eurovision, the Olympics, and the World Cup to launder their reputations on an international stage.

As Olympics scholar Jules Boykoff puts it, sportswashing refers to the ways “political leaders use sports to appear important or legitimate on the world stage while stoking nationalism and deflecting attention from chronic social problems and human rights woes on the home front.”

States can distract audiences from violence or other political problems through spectacle and the promise of escapism. This is often achieved through staging lavish opening ceremonies that purport to “welcome” international audiences even as host states restrict who is physically or socially welcomed to the events – and happens in authoritarian regimes and democracies alike.

Additionally, music and politics scholar Marco Basioli explains show states use the positive, celebratory atmospheres and branding of an event to produce “acceptable instead of unpleasant representations” of their country. He points to the example of Russia’s decision to send Manizha, a Russian-Tajik feminist and pro-LGBTQ+ activist, to Eurovision in 2021 in order to create the impression that the state accepted progressive values.

The emphasis in sport- and culturewashing scholarship is often on the actions of the governments trying to hide or change perceptions of the violence and human rights abuses they are committing.

The emphasis in sport- and culturewashing scholarship is often on the actions of the governments trying to hide or change perceptions of the violence and human rights abuses they are committing. But a key part of the reason that states can use mega-events for political gain so effectively is because the event organisers let them. FIFA’s decision to award US President Donald Trump with “a peace prize” in December is one particularly absurd recent illustration of this process, but Eurovision is not far behind.

In other words, to understand how culturewashing works, we also have to pay attention to complicity. Complicity generally refers to being indirectly involved in wrongdoing or harm. Philosopher Hannah Arendt, for example, made a distinction between guilt (directly committing harm) and responsibility (taking responsibility for being part of a community that allowed harm or failed to prevent it).

In the context of mega-events, this means that organisers like the EBU are making a choice to provide a platform for genocidal states, which allows the states to normalise their actions in the international arena.

Non-political entertainment

The EBU goes to great lengths to try to hide its role in enabling Israel’s participation and avoid accountability. The most obvious way it does this is by claiming the contest is both “non-political” and “an entertainment show”. In April 2024, then-Executive Supervisor Martin Österdahl explicitly cited Eurovision’s status as entertainment to justify the contest’s supposedly “non-political” stance:

“We understand that people are concerned, but ultimately this is a music show, this is a family entertainment show, and we should focus on that. We are not the arena to solve a Middle East conflict.”

This rhetorical move downplays Eurovision’s active role on the geopolitical stage, including endorsing Israel’s participation. It also positions the contest as “harmless fun”, creating distance between the contest’s actions and responsibility for the broader political consequences of those actions.

In a single statement, the EBU managed to diminish the influence of the competing artists in order to absolve them of responsibility for participating, as well as dismiss the legitimate criticisms of fans and activists by framing them as bullies.

Since 2024, the EBU has expanded this rhetorical power beyond basic claims to neutrality to discursively restrict how responsibility and complicity can be framed in relation to Eurovision. In the months leading up to the Malmö edition of the contest, for example, many Eurovision fans, along with the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement and other activist groups, sent letters and petitions urging competing artists who had publicly expressed support for Palestine to withdraw.

In response, the EBU issued a statement chastising fans for engaging in “targeted social media campaigns against some of our participating artists.” The statement accused fans of “online abuse, hate speech, [and] harassment,” calling the public pressure “unacceptable and completely unfair, given the artists have no role in this decision.”

In a single statement, the EBU managed to diminish the influence of the competing artists in order to absolve them of responsibility for participating, as well as dismiss the legitimate criticisms of fans and activists by framing them as bullies. In doing so, the EBU constricts who can be seen as complicit, and what they are complicit – or not complicit – in.

In the December General Assembly meeting last year, the EBU deployed this tactic again by tying the already twice-delayed vote on Israel’s participation to the separate question of voting reform. This put the question of whether a state committing genocide should be allowed in the competition on the same footing as reforms to the integrity of the televoting system, reducing the political and humanitarian concerns raised by countries such as Slovenia and Spain to a technocratic procedural matter.

Reframing boycott as an individual choice

Slovenia, Spain, the Netherlands, Ireland and Iceland have withdrawn from the 2026 contest in protest. The Netherlands and Ireland have participated in the contest since its inception, and Ireland is one of the contest’s most successful participating countries – joint record holder for the highest number of wins (7, with Sweden), and the only country to have won three times consecutively. Spain and the Netherlands are also some of the contest’s largest financial contributors, paying in recent years approximately €330,000 and €250,000 in participation fees, respectively.

Despite this, the EBU is claiming the outcome of the December meeting as a victory. The EBU announced the result of the meeting in a statement declaring that “EBU Members show clear support for reforms to reinforce trust and protect neutrality of Eurovision”. Eurovision’s Executive Director, Martin Green, likewise claimed that the meeting reaffirmed “the belief that the Eurovision Song Contest shouldn’t be used as political theatre.”

The EBU is already trying to undermine the impact of the withdrawals by framing them as individual choice rather than principled action.

The fact that the EBU is willing to let these countries withdraw to protect a state committing genocide lays bare the lengths Eurovision will go to in order to maintain its relationship with Israel. The EBU is already trying to undermine the impact of the withdrawals by framing them as individual choice rather than principled action.

As Green noted in an interview following the meeting, “that’s their choice, I completely respect that.” Green also undermined the impact of the withdrawing states’ intention not to broadcast the contest next year by promising that the EBU will “fully make sure that the fans and the audiences can watch the show.”

Resisting complicity: Partial and total boycott

All of these decisions put audiences and artists in an unenviable position. The EBU has the authority to remove countries that do not live up to the contest’s stated values and broadcasting standards, as it did with Russia in 2022 and Belarus in 2021.

The national broadcasters had the procedural power at the EBU General Meeting to demand two separate votes – one for Israel’s participation and one for televoting reform. The broadcasters also still have the power to stand for what is right and make the contest financially unviable by joining the boycotting countries and demanding Israel’s exclusion. By refusing to act, the EBU and national broadcasters force individual fans to choose either to give up something they love, or to keep watching and be made complicit in the normalisation of genocide.

Eurovision fans enable Israel’s culturewashing campaign by continuing to watch and engage with the contest. As fan studies scholars such as Matt Hills explain, fans are not just avid followers of sport and culture, they are consumers, with the capacity to choose where and how they spend both their money and their attention, including to lobby for social or political change.

When Eurovision fans buy tickets to the live shows, buy merchandise, or participate in televoting, they are directly contributing to the financial success of the contest, and tacitly endorsing (or at least, not entirely rejecting) the decisions of its organisers.

The broadcasters also still have the power to stand for what is right and make the contest financially unviable by joining the boycotting countries and demanding Israel’s exclusion.

Many Eurovision fans recognise this financial link and have started engaging in what they call “partial boycott”, still watching but no longer spending money. This can be an important first step in individual fans’ processes of distancing themselves from an event they believe is no longer living up to the values they care about.

Yet even watching at home still indirectly enables culturewashing by providing Israel with an audience and allowing the EBU to claim the event is as popular as ever. According to the EBU, 166 million people tuned in to Eurovision in 2025 – 3 million more viewers than in 2024.

In contrast, total boycott that disrupts the viewing figures, and related actions such as attending alternative events or campaigning to persuade more national broadcasters to withdraw if Israel participates, make it much more difficult for Eurovision and Israel to claim that the contest is continuing as normal.

The boycott gains momentum

As difficult as navigating individual and collective complicity in enabling culturewashing can be for many fans, there is still hope. The five boycotting countries have dealt a massive reputational and financial blow to Eurovision. It is especially humiliating that, with only 35 participating countries confirmed, the 70th anniversary of the event will be its smallest edition since the introduction of the semi-final in 2004.

The withdrawals are also an important victory for the BDS movement and for Palestine. Slovenia, the Netherlands, Ireland, Spain and Iceland have sent a clear moral message that they will not party with genocidaires. Emboldened by their action, many fans and artists have expressed their intention to boycott.

With only 35 participating countries confirmed, the 70th anniversary of the event will be its smallest edition since the introduction of the semi-final in 2004.

Other countries and fan communities may yet follow suit, and the more people and countries join the boycott, the more the EBU will feel the pressure to exclude Israel. That momentum will also build around other international sporting competitions and cultural events in which Israel participates.

In an interval act during the 2025 Eurovision in Basel, one of the show’s hosts, Hazel Brugger, delivered a lyric that tellingly exposed the impact of Eurovision’s supposed apolitical stance: “non-political, strictly neutral / doesn’t matter if you’re good or brutal”. The more the EBU doubles down on the claim that Eurovision’s non-political stance allows it to unite through music, the more it shows us that what Eurovision has chosen to be united with is genocide and occupation.

Zoë Jay is a Kone Foundation-funded researcher in international politics at the Centre for European Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on fan communities and the politics of international mega-events.

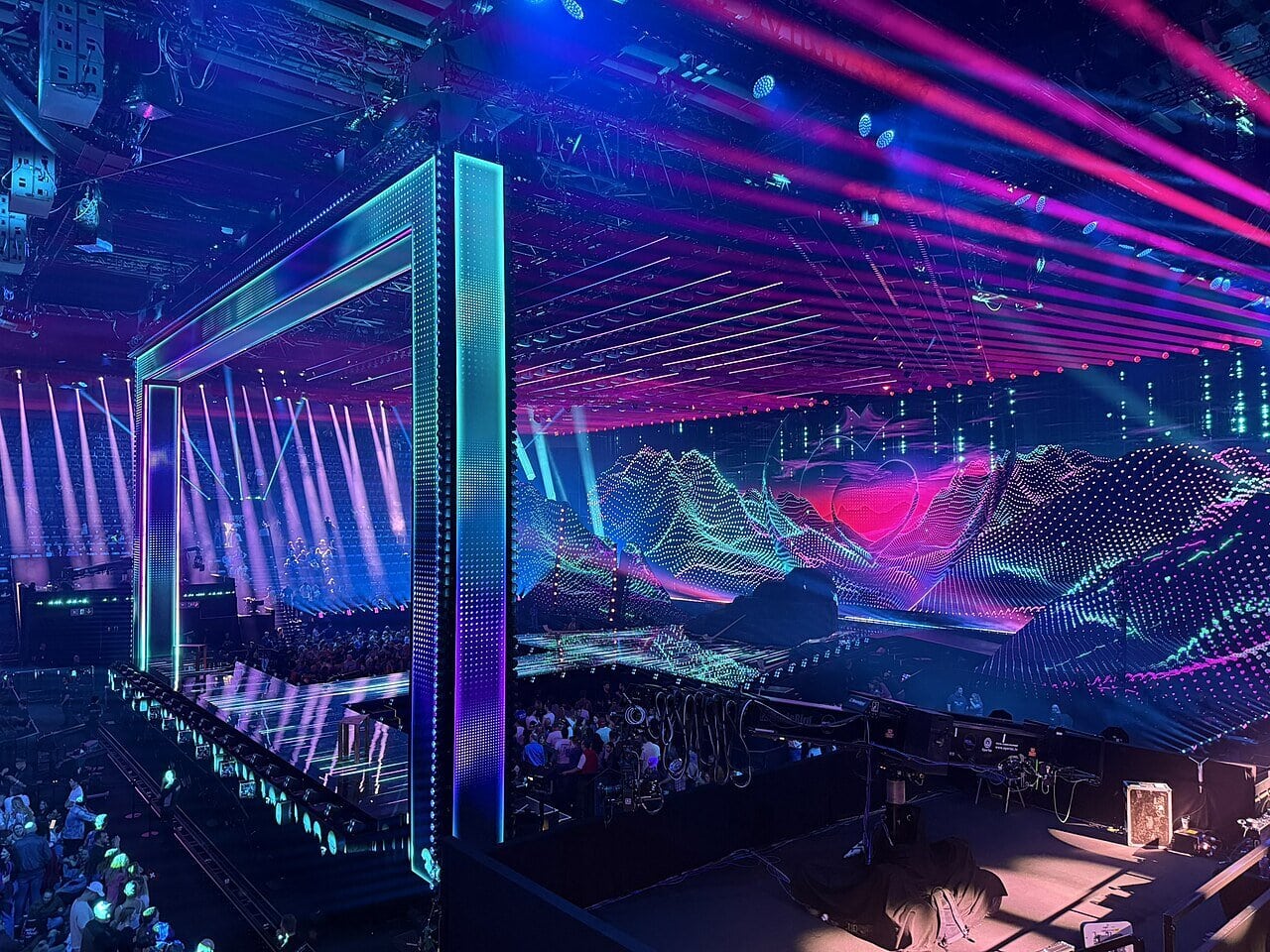

Article image: The stage of the Eurovision Song Contest 2025 in Basel, Switzerland / MrSilesian / Wikimedia Commons CC0