European identity is an important political tool for the European Union. Even though we can never find an adequate definition for it, it is crucial to keep discussing it and its various interpretations and meanings.

The presidency of the Council of the European Union (EU) rotates among the member states every six months. The Council is a key decision-making body within the EU, representing the member states’ governments. The host states of the presidency commonly organise conferences delving into contemporary European issues and timely debates.

This spring, the host country, Belgium, invited two hundred European cultural policymakers and representatives of cultural and heritage institutions and networks to a conference entitled “Unity in Diversity? Culture, Heritage and Identity in Europe” to discuss “the role of culture and heritage in the formation and expression of European identity.”

During the past decade, many previous hosts have organised conferences on the same topic. This article discusses why the EU is fascinated with European identity and what it does with it. The approach to the topic draws on my previous research projects exploring EU cultural and heritage initiatives and their governance.

The project results broaden the view of the topic by including in the discussion citizens’ notions of Europe and European identity. The article is based on my talk at the above-mentioned conference in Antwerp, taking place from the 15th to the 16th of April 2024.

Competing European projects

EU communication often refers to a European project. It means the EU’s aspirations towards a unified, collaborative, prosperous, and peaceful Europe based on common values and an identity drawing on shared culture and heritage.

The idea of linked European culture, heritage, and identity has obsessed European policymakers since the establishment of the European Community in 1957. The idea has remained topical due to various social, political, economic, and humanitarian challenges or crises that the EU and its European project have faced during the past decades.

The EU is not the only actor interested in a European project. The narrative of Europe as a distinct area with common values, culture, and heritage is attractive to many different groups.

The EU is not the only actor interested in a European project. The narrative of Europe as a distinct area with common values, culture, and heritage is attractive to many different groups. These include the European Identitarian Movement, which is an ethnocultural movement asserting the cultural and territorial rights of European-descended peoples, and many radical right-wing parties.

They seek to promote an exclusive idea of Europe and thus justify their xenophobic, anti-immigration, antisemitic, Islamophobic, and racist attitudes and actions. This kind of narrative contradicts the EU’s inclusive European project, which seeks to increase dialogue, inclusion, and a sense of belonging among all people living in Europe.

Tackling challenges with culture and heritage

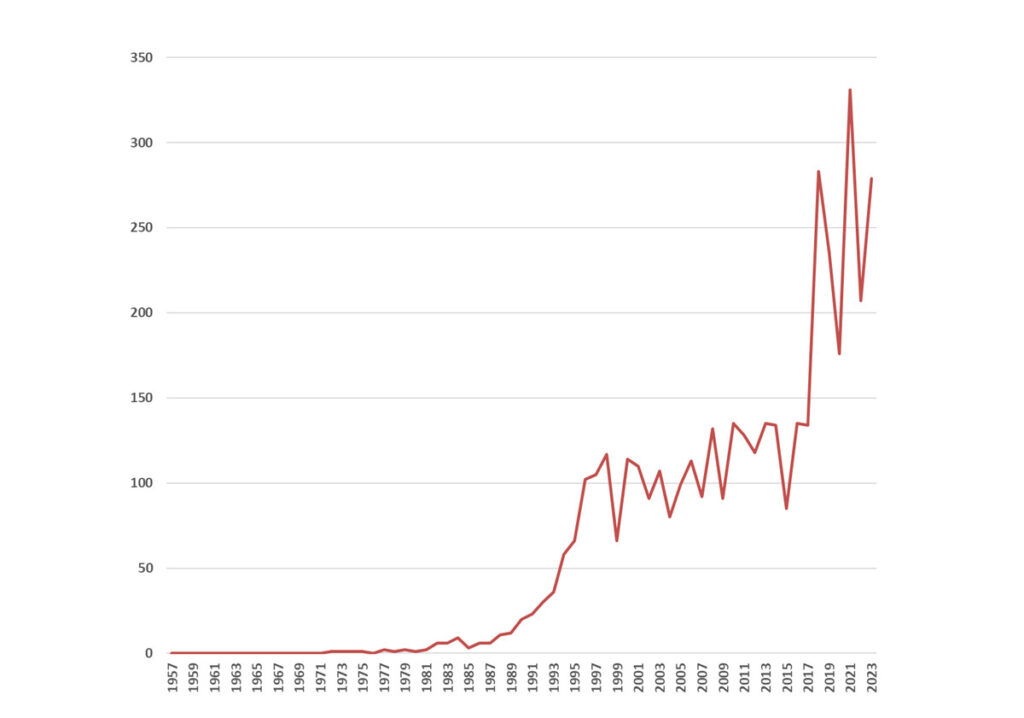

For the European policymakers, culture and heritage are instruments to tackle the challenges impacting the EU’s European project. This is reflected, for instance, in the European Commission’s increasing interest in cultural heritage in its policy discourse (see Figure 1). During the past decade, the Commission has launched several new policies, actions, and initiatives addressing cultural heritage.

Besides the Commission, the European Parliament has been active for decades in supporting the preservation of cultural heritage and communication about Europe’s cultural memory and history. The House of European History, the Parliament’s history museum, opened in Brussels in 2017, is a flagship of these activities.

Figure 1. Increase of documents (n = 4212) including the search term ’cultural heritage’ in the EU’s official document database EUR-Lex under the domain ’EU law and case law’ from 1957 to 2023. Seven hits from 1957 have been ignored as these documents were consolidated versions of EU treaties dating from 1997 to 2010. © Tuuli Lähdesmäki

Many of the EU’s cultural and heritage initiatives have ambitious objectives, such as “counter[ing] racism and xenophobia and encourag[ing] greater tolerance for other cultures across Europe” and “invit[ing] Europe to respond to the social, political, and economic challenges of the culture sector“, as the European Commission’s website describes the aims of the European Heritage Days.

The key political utility of culture and cultural heritage draws on their potential effect on people’s feelings. Professor Kiral Klaus Patel has underlined this aspect by noting how EU cultural policy is designed “to win the hearts and minds” of European citizens. The policy discourse in the EU’s broad cultural programmes, such as the current Creative Europe programme, explicitly refers to European identity and defines the strengthening of it as one of the priorities of the programme.

Since the 1990s, several scholars have criticised the concept of identity for emphasising it as fixed instead of a process in which our understanding of ourselves and others constantly transforms.

In addition to European identity, many EU cultural and heritage initiatives seek to “increase citizens’ sense of belonging to a common cultural area”, as the decision of the European Capital of Culture says, or aim at “strengthening European citizens’ sense of belonging to the Union” and “common space”, as the decision of the European Heritage Label says.

The emphasis on belonging in EU policy discourse reflects the conceptual debate on identity in scholarship. Since the 1990s, several scholars have criticised the concept of identity for emphasising it as fixed instead of a process in which our understanding of ourselves and others constantly transforms.

These scholars, such as Elspeth Probyn, Marco Antonsich, and Nira Yuval-Davis, have noted how the concept of belonging enables us to capture more accurately people’s changing needs and desires for attachment to other people, places, or modes of being. Belonging is a less definitive concept: one may feel belonging to something, such as Europe, but may not necessarily identify with it, and thus does not have European identity.

What do the participants in EU cultural initiatives think about Europe?

My research team and I have studied how people participating in EU cultural initiatives perceive the European dimension of culture and how they associate with Europe. The first of these studies explored the visitors of three European Capitals of Culture: Pécs2010 in Hungary, Tallinn2011 in Estonia, and Turku2011 in Finland.

The European Capital of Culture is the EU’s flagship cultural initiative, wherein the European Commission annually designates European cities with this title. The data for this study included 1425 survey responses gathered among the visitors to cultural events in the cities.

The responses revealed diverse ways of perceiving ‘the European’ in the European Capitals of Culture. The most common responses addressed the respondents’ everyday experiences of encountering European people – artists, performers, and visitors from other European countries – and enjoying works of art and events created or produced by such artists and performers.

The lack of history in the responses can be interpreted in several ways. For instance, history is often related to identity formation at the national, not the European, level.

Moreover, the respondents recognised and identified ‘the European’ through whatProfessor Michael Billig calls “banal” forms of culture. These forms included well-known symbols of the EU, such as the EU flag, and easily recognised features of diversity in Europe, such as people speaking and performing in foreign languages. ‘The European’ was, thus, mostly perceived from a pragmatic point of view and not drawing on the content of culture.

The respondents rarely discussed ‘the European’ as based on common European culture, history, heritage, traditions, monuments, or historical sites. When they did, they were likely to be highly educated. In general, the notions of ‘the European’ in the data were notably non-historical.

The lack of history in the responses can be interpreted in several ways. For instance, history is often related to identity formation at the national, not the European, level. History, heritage, and traditions were indeed more often discussed in the data related to local, regional, and national culture.

Two approaches to Europe

The second study focused on the European Heritage Label, the EU’s flagship heritage initiative through which the European Commission biannually awards European cultural heritage sites. The study included 271 visitor interviews conducted in 2017 and 2018 at 11 labelled sites in ten European countries. The interviews reveal two main approaches to Europe, namely the ‘Europe of people’ and ‘Europe of nations’.

The first approach is characterised by pragmatism: the interviewees emphasised people’s personal agency and potential to contribute to making Europe. For them, the notion of Europe commonly drew from their experiences of being mobile in Europe and connecting and interacting with people with diverse national and cultural backgrounds.

The interviewees also were asked to describe what European identity is like and whether they feel European themselves. Most of the interviewees felt European, but it was much more difficult for them to describe European identity.

In the second approach, the interviewees underlined Europe as an entity consisting of bounded geographical areas, such as nations and regions, with specific cultural characteristics. These interviewees greatly valued the cultural and national differences inside the EU and regarded them as worth preserving.

The interviewees also were asked to describe what European identity is like and whether they feel European themselves. Most of the interviewees felt European, but it was much more difficult for them to describe European identity. Some of them criticised the concept for being too restrictive and having exclusive and static connotations.

Let’s keep talking about European identity

There is a broad body of literature seeking to define Europe, ‘the European’, and European identity. Some scholars have identified different models of understanding European identity, such as cultural, civic, political, and pragmatic models. Others have sought to identify certain historical phases and phenomena, such as Hellenist aesthetics, Roman law, Christianity, and modernity, characterising European culture and identity.

In recent literature, Europe is commonly perceived as a conceptual entity that has been both historically and philosophically a “moving target” and, thus, so “elusive that it is doubtful whether [it has] any reality at all outside the imagination”, as scholars Ullrich Kockel, Máiréad Nic Craith, and Jonas Frykman have noted.

In recent literature, Europe is commonly perceived as a conceptual entity that has been both historically and philosophically a “moving target”.

Europe is an idea, discourse, and narrative, and thus, there are several Europes and European cultures, heritages, and identities. We cannot ever find a final definition of them since they are plural and constantly transforming. All definitions are inevitably exclusive and inadequate.

More important than finding definitions is, that we keep discussing Europe, ‘the European’, and European identity, and that diverse people in Europe participate in these discussions and bring to the debates their views and experiences.

Moreover, it is crucial that all of us are willing to listen to others’ views and experiences, have a dialogue with them, and broaden our own understanding of Europe. The key role of the EU in this is to support actors and projects seeking to create spaces, events, and platforms for such discussions, listening, and dialogue.

PhD, DSocSc Tuuli Lähdesmäki is an associate professor of art history at the University of Jyväskylä.

Article image: Antoine Schibler / Unsplash