The 57th edition of the Venice Biennale opened on Saturday 13 May 2017. For an International Relations scholar, the Biennale offers an opportunity to explore the structures of the art world and observe the dynamics between different kinds of actors.

Considering its characteristic practice of national pavilions, many of them owned by the exhibiting states, the Biennale embodies international relations and geopolitics on the very surface level. Its politics, however, are more complex as this article based on my field trip to the preview week of the Biennale shows.

Regularly reoccurring art biennials have proliferated since the 1990s. Researchers have tried to define and conceptualise the essence and mechanisms of “biennalisation”.

The Biennale embodies international relations and geopolitics on the very surface level.

Some see biennalisation as a “global” phenomenon able to open up new spaces of resistance, diversity, reflection and cross-fertilisation of ideas. They conceptualize biennials as a mechanism of “a democratic redistribution of cultural power or examine the capacity of biennials to create “new worlds” through art. Biennials may also be argued to offer opportunities for resistance and discussions about alternative worldviews.

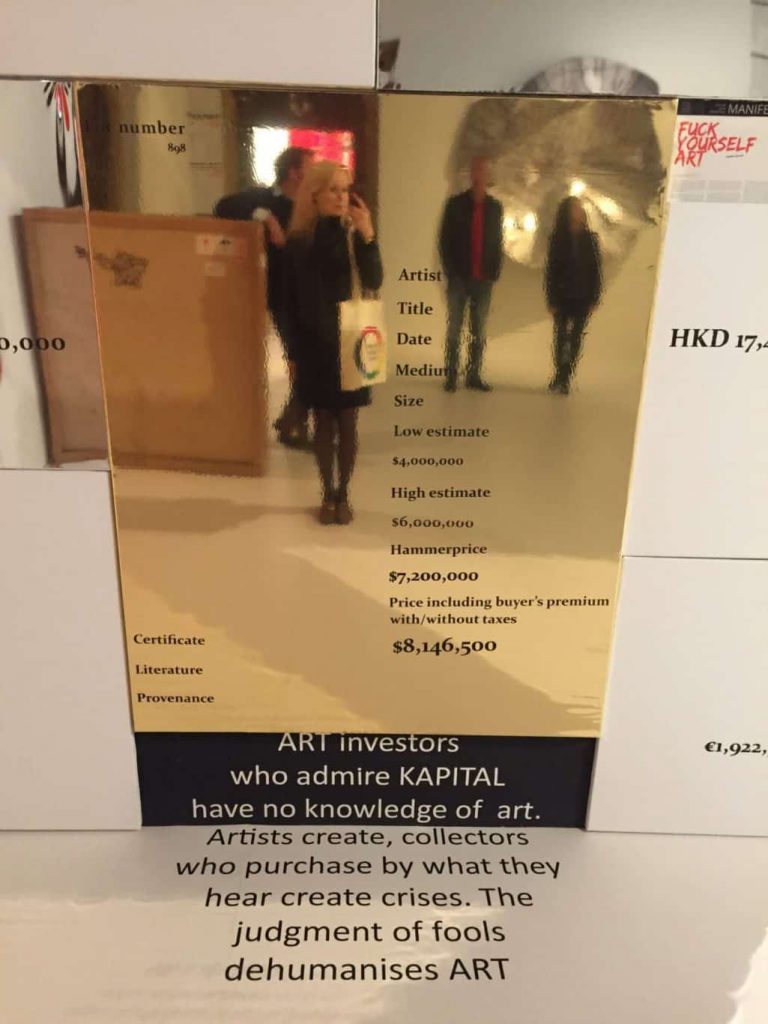

Others examine biennials in the context of the capacity of neoliberal globalisation and culture industry to banalise, standardise and instrumentalise contemporary art. In this interpretation, biennials subjugate the arts to commodification and to demands of political and economic convenience.

Biennials have also been accused of being fundamentally unequal institutional mechanisms, which embody “the traditional power structures of the contemporary Western art world”.

Depending on one’s point of view, all these dynamics can be detected at the Venice Biennale, the oldest and most prestigious of the world’s art biennials, dating back to 1895.

Contemporary art in a complex world

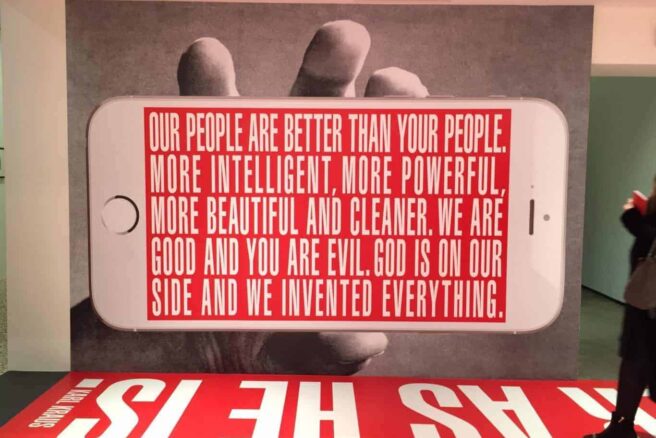

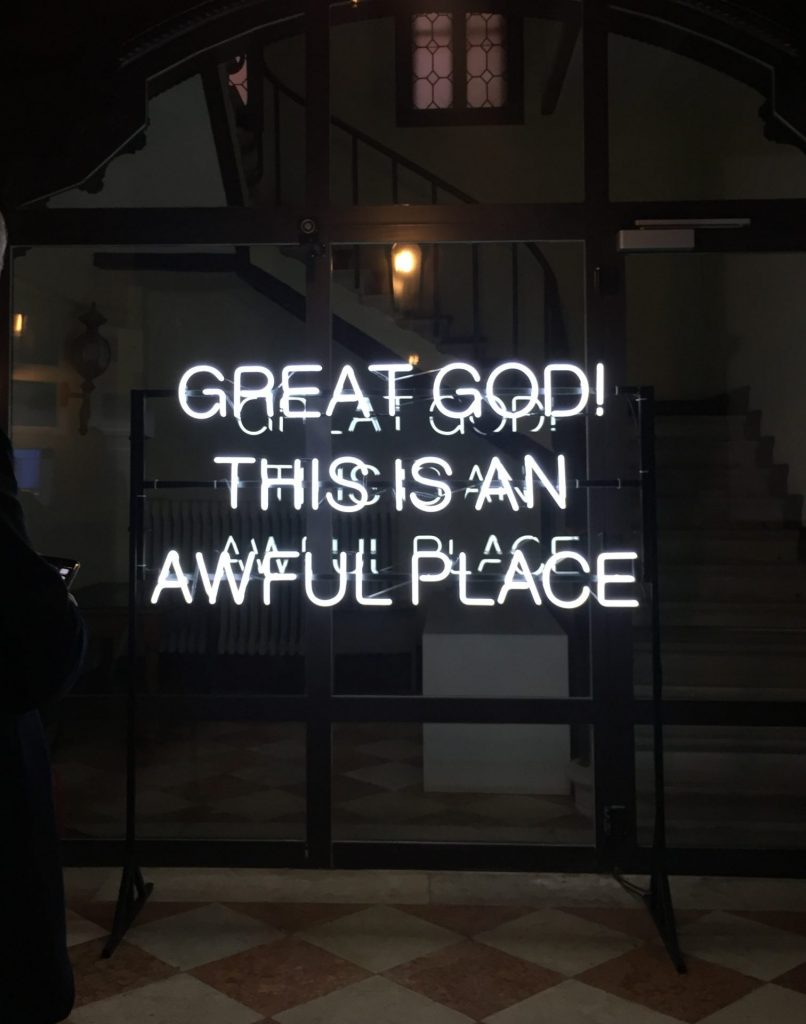

This year the theme of the Biennale is ‘Viva Arte Viva’, which implies that “through art, [the Biennale] celebrates mankind’s ability to avoid being dominated by the powers governing world affairs”.

The 57th edition of the Venice Biennale thus highlights the role of art and artists in the times of uncertainty. It suggests that art has a capacity to reach beyond the political systems and crises generated by them.

The Biennale’s curator Christine Macel, who is also the chief curator of the Centre Pompidou, argues that “[t]oday, faced with a world full of conflicts and shocks, art bears witness to the most precious part of what makes us human, at a time when humanism is precisely jeopardized. […] At a time of a global disorder, art embraces life, even if doubt ensues inevitability. The role, the voice and the responsibility of the artist are more crucial than ever, within the framework of contemporary debates”.

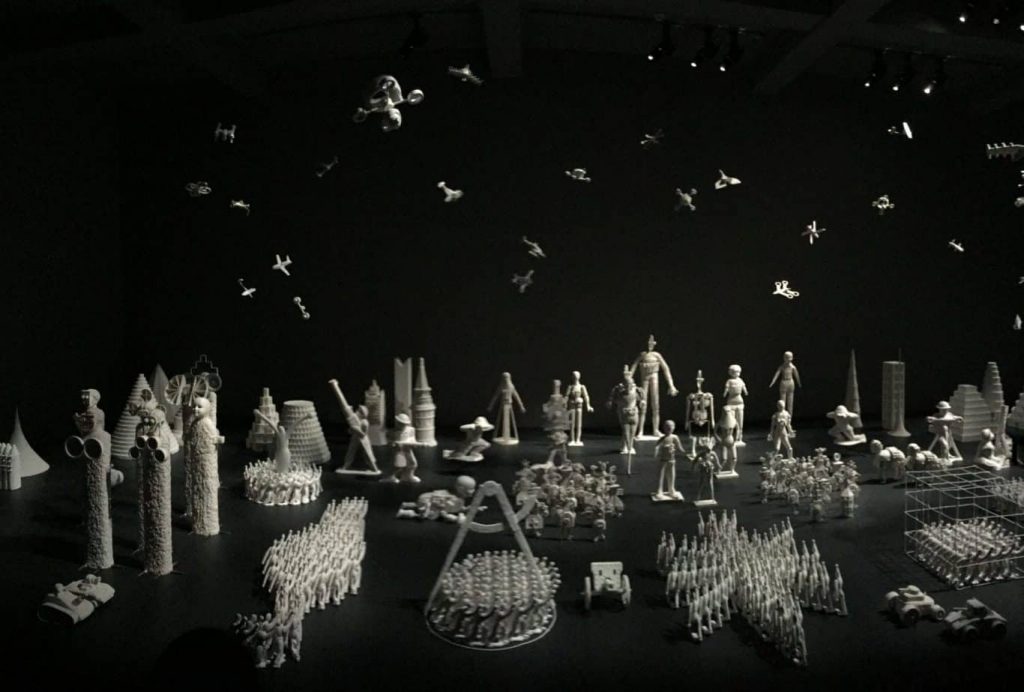

A wider tone of uncertainty could also be detected in some of the Biennale’s exhibitions. For instance, the Russian pavilion, having changed its organisational team from the previous three art Biennales, discussed global uncertainty in its exhibition ‘Theatrum Orbis’. This was especially strongly expressed in one of its three exhibitions, titled ‘Scene Change’ by artist Grisha Bruskin.

The 57th edition of the Venice Biennale suggests that art has a capacity to reach beyond the political systems and crises generated by them.

Bruskin’s dimly lit exhibition on the upper floor of the pavilion presented a mix of sculptures and multimedia, involving also music and changing lighting. The exhibition discussed the “new emerging world order where growing aggression, terror, the irrational life of the masses and the unprecedented control and monitoring strategies permeate the life of our contemporaries”.

On the preview opening day of the pavilion, the exhibition guides were telling to the curious crowds about the meaning of the work, explaining its reference to the Syrian Palmyra, among other places. A few preview visitors I talked to found the Russian pavilion a little too straightforward. Many also praised its comprehensibility.

The Australian pavilion also made a rather straight-forward point, but mainly thanks to its extra-pavilion activities. The pavilion presented works by Tracey Moffatt, the first indigenous artist to be exhibited in the Australian pavilion since 1997.

In one of the ‘My Horizon’ exhibition’s video works the theme of asylum and refugees was touched upon, showing images from the refugees-packed boats. The viewers were introduced to this thematic already while queuing at the entrance of the pavilion, where everyone was offered a black canvas bag with a political statement on both of its sides.

One side of the bag said ‘Indigenous rights’, written with bright yellow text, while the other side of the bag proclaimed ‘Refugee rights’ in red. Soon both Giardini and the streets of Venice were filled with people carrying these bags, spreading the bags’ messages intentionally or unintentionally.

However, it was intriguing to notice that while many people were carrying the bags throughout the preview days, the majority preferred to display the yellow ‘Indigenous rights’ side of their bag.

Politics of visibility

Before the official opening on Saturday 13 May, the main exhibition sites of Giardini and Arsenale were buzzing with people: the three-day preview drew together artists, critics, art collectors, sponsors and individual guests who had gained an access to the exclusive event.

As Sarah Thornton argues in her book Seven Days in the Art World (2008), “[w]ith 34,000 VIP and press passes issued for the four-day event, the Biennale is the world’s largest single assembly of art world insiders and their observers”.

When the Biennale officially opens and the awards ceremony takes place, most of the preview visitors already leave Venice, having seen everything before the public. Thus, curiously, when the Biennale officially begins, for many art world actors it has already ended.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Biennale is, indeed, its peculiar politics of visibility consisting of exclusive parties, collateral events, social media visibility and celebrities.

The majority of the exhibition openings and exclusive parties take place on the three-day period before the official Biennale opening, filling the preview visitors’ schedules with events organized both by the participating countries and collateral events, which are an integral part of the Biennale’s structure.

The collateral events are often organised by non-profit public or private institutions wishing to gain symbolic capital in the form of recognition and visibility. The label of a collateral event, which gives the right to be part of the Biennale’s official programme, is worth tens of thousands of euros.

One of the collateral event participants this year was the Moscow-based Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, which organized a vibrant opening reception with a performance by Olga Kroitor in the gorgeous Palazzo Soranzo Van Axel. The exhibition ‘Man as a Bird. Images of Journeys’ will remain open until September, reflecting the museum’s ambitions to work with new media and relate “Russian and the international art process”.

Among the organisers of collateral events this year were also Fondation Louis Vuitton, which opened its first contemporary art center in 2014, and Victor Pinchuk Foundation, the latter of which presented the fourth edition of its annual ‘Future Generation Art Prize @ Venice’ throwing a trendy reception party for its carefully crafted guest list. These examples illustrate that the Biennale gives visibility and, perhaps, legitimacy in the art world to a set of very different actors.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Biennale is its peculiar politics of visibility consisting of exclusive parties, collateral events, social media visibility and celebrities.

Besides the official Biennale programme, the opening week is rich with events organised by unofficial participators that are not officially linked to the Biennale. Depending on the format, these organizers target the high-capital preview visitors and Biennale tourists by organising events simultaneously with the Biennale’s programme.

For instance, the comeback exhibition of Damien Hirst opened in April in both of the two museums owned by François Pinault, making Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana important stops for the Biennale crowd. Unsurprisingly, the photographs of Hirst’s exhibitions were widely shared on Biennale preview visitors’ social media accounts. As Hirst’s exhibitions run until December, they can be expected to become popular spots for art tourists in Venice in 2017.

One interesting edition benefitting from the Venice Biennale and the high concentration of the art world’s elite in the city was the art foundation V-A-C, owned by one of Russia’s richest people Leonid Mikhelson.

The Venice Biennale has become a special setting for many wealthy Russians who are drawn into the world of contemporary art and establish art centers, museums and private galleries both in Russia and abroad. But the cozy relationship between contemporary art and extreme wealth is not a Russia-specific phenomenon. Contemporary art has for a long time been a field of interest of the wealthy: there is, for example, a strong American tradition of art patrons and private museums specialising in contemporary art.

The brand new Venetian headquarters in the four-leveled Palazzo delle Zattere was busy on a Thursday afternoon, packed with famous art dealers, art collectors, businessmen and high-profile Russian socialites celebrating the opening of the new venue and its exhibition ‘Space Force Construction’.

A performance by Taus Makhacheva was taking place in the staircase of the museum and a high number of security were guarding the exhibition rooms, perhaps partly due to the significant amount of the “high net-worth individuals” visiting the art center.

From national to supranational pavilions

One of the most defining but also most debated features of the Venice Biennale is its organisation into national pavilions and the tradition of awarding the best national pavilion with the Golden Lion prize. Due to its national and competitive elements, the Biennale is often designated as “the Olympic Games of the Art World”. Each year the number of new participating national pavilions has been increasing, resulting in the national participation of 86 countries in 2017.

It is thus curious that next to the V-A-C event the Antarctic pavilion, “the Venice Biennale’s first ever supranational pavilion”, was celebrating its opening night. The outcomes of the first Antarctic Biennale, which was organized in March–April 2017, were presented to the international – but predominantly Russian-speaking – opening party audience that enjoyed the celebrative, yet laid-back atmosphere on the green courtyard of the exhibition venue.

The guests of the opening consisted of a rather heterogeneous group, ranging from hip 20-somethings to art dealers and gallerists in their smart attires. Also the commissioner of the Antarctic pavilion and the biennale Alexander Ponomarev, who has been said to be the initiator of these projects, was actively present in the opening.

Art meets research

Within academia, there is a growing interest toward artistic research. The Venice Biennale also highlights its research-driven essence. The President of the Biennale Paolo Baratta defines “La Biennale as a place for research” and continues that this year the Biennale “introduces a further development” by making the method of the Biennale, that is, the open dialogue between the artists and the public, as the theme of the Biennale’s International Exhibition.

Baratta highlights art’s informative and educative function, stating that the 57th Biennale is dedicated to “celebrating, and almost giving thanks for, the very existence of art and artists, whose world expand our perspective and the space of our existence.

Besides the Biennale’s International Art Exhibition, the Biennale incorporates several research platforms.

These are not just words. Besides the Biennale’s International Art Exhibition, the Biennale incorporates several research platforms as, for instance, the Research pavilion on the island of Giudecca, and the transdisciplinary, socially engaging art project Dark Matter Games, situated in Dorsoduro.

The Research pavilion is created and hosted by the Helsinki-based University of the Arts. The Research pavilion will host three exhibitions: the first one is a Nordic collaboration, whereas the following two exhibitions will be organised by the Zurich University of the Arts (July–August) and the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (September–October).

Political economies of the Biennale

Besides art exhibitions and performances taking place during the Venice Biennale, the role of sponsors is another notable feature in the politics of the Biennale. This year JTI (Japan Tobacco International) was among the main sponsors of the Biennale. JTI made itself visible by giving out special souvenirs, black pocket ashtrays, to the Biennale’s preview guests in Giardini and Arsenale. Also, illycaffé as a sponsor and Swatch as a partner had visible presence at the Biennale.

Illycaffé not only served free espressos in Giardini but also participated in the Biennale with an exhibition site in Dorsoduro. The fields of commerce and art were intertwined as the artwork of contemporary artist Robert Wilson were mixed with presentation of The illy Art Collections, a series of artistic coffee cups designed in collaboration with different artists.

Swatch, on the other hand, had its own brightly colored stage in the popular café area in Giardini, advertising its limited-edition watch, also designed in collaboration with an artist. The advertisement signboard tried to embrace the artistic essence of the new watch, stating that “[o]nce more bringing art to the real life of people, it contributes to spread the ‘Swatch Loves Art’ message that contributes to inspire and animate a unique creative dialogue”.

Pascal Gielen has argued that the Venice Biennial has become a “hybrid monster”. Born as the promoter of the nation-state and nationalist agendas, the Biennale has now been enthusiastically embraced by sponsors, managers, politicians and others.

The hybridisation of the Biennial was well visible at the opening reception of the Russian national pavilion organized at the Mercati di Rialto fish market. The walls of the space were covered with the advertisements of the pavilions’ sponsors: Arts Newspaper, Vogue, the vodka brand Beluga and the luxury department store Tsum were all there.

It was as if the movements of the “monster” were, for a moment, embodied in the vibrant mix of artists, politicians, critics, journalists, businessmen and socialites dancing to the rhythm of music played by Denis Simachev, the famous Moscow-based clothing designer, from behind his glossy, Beluga-branded DJ’s deck.

Julia Bethwaite is a doctoral student in International Relations in the Faculty of Management, University of Tampere, Finland, and a member of the research projects ‘Cultural Statecraft in International Relations: The Case of Russia’ (Academy of Finland) and ‘Spaces of Justice Across East-West Divide’ (Kone Foundation). She explores the role of art in international relations with a focus on Russian actors in the transnational field of art, examining practices of cultural diplomacy, transnational cultural relations and the interaction of state and non-state actors within the field of art.