Can the newly elected president of Indonesia offer real reform, or will the election results simply reinforce Indonesian politics as usual?

The new Indonesian president for the office term 2019–2024 has just been inaugurated on Sunday, October 20th 2019. President Joko Widodo, colloquially known as Jokowi has been re-elected for his second and final term as the head of a country with a population of 270 million.

Jokowi’s presidency is supported by the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP) ─ chaired by Megawati Soekarnoputri, a daughter of the Indonesian founding father and first president, Sukarno ─ which had 19% votes in previous, 2014 election.

As the requirement for nominating presidential candidates, the political parties must have at least 20% support from parties in the parliament. Thus PDIP formed a coalition, with old parties such as Golkar and PPP and others.

Golkar was established during Suharto’s New Order regime and gained the prominent position as the main state political party, holding the loyalty of the civil servants and the military. Since 1999, Golkar’s privilege has been abolished but it remains a strong political party.

PPP or United Development Party is an Islamic political party that has also existed since the New Order regime, uniting Islamic groups in the country during Suharto’s rule. Today, PPP struggles to compete with other Islamic parties to gain votes.

Jokowi’s nomination secured the support of 60% of parties in the parliament. Jokowi’s previous rival, Prabowo Subianto, had 40% party support in the parliament, from Prabowo’s own party Great Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra) and an Islamic party, the Prosperous Justice Party or PKS. Thus, heading into the presidential election, Indonesian voters were practically captured between just two blocks.

Indonesia has a strong presidential system, meaning that the directly elected president has prerogative right to choose ministers for his/her cabinet. Three days after his presidential inauguration, Jokowi announced his new cabinet members, and the position Minister of Defense was given to his presidential rival, Prabowo.

This decision has sparked tension and disappointment among Jokowi supporters, because the presidential campaign was extremely fierce and polarizing, continuing the trend from 2014 of almost dividing citizens into two camps.

In Indonesian politics, it is quite common that a political rival becomes a supporter at another time. The election in Indonesia is more about “personalities rather than parties”.

It is hard to differentiate certain ideology among parties other than Islamic or non-Islamic party, because all parties claim to be democratic. This may lead to fairly shifting electoral coalitions.

For example, in 2009, Prabowo was nominated as the running mate (vice president) of Megawati’s presidential nomination, due to the Gerinda’s party problems in reaching the 20% threshold for presidential elections.

At that time, Prabowo’s background as human right violator, with close connections to the old authoritarian and corrupt regime of president Suharto was disregarded by Megawati. Yet, during 2014 presidential debate, the Prabowo’s issues with human right were brought up again.

In the latest 2019 election, this issue was neither discussed by Jokowi nor Prabowo. Thus, if Jokowi offered Prabowo and his political party positions in the cabinet, the question is: does it show ‘politics as usual’ in Indonesia or is it part of Indonesian democracy?

Behind the presidential election 2019

The Indonesian national elections determine a president and vice-president, 560 national legislative members and around 2 000 members of local parliaments (from 34 provinces and 500 districts or municipalities), all held on the same day, most recently on April 17th 2019.

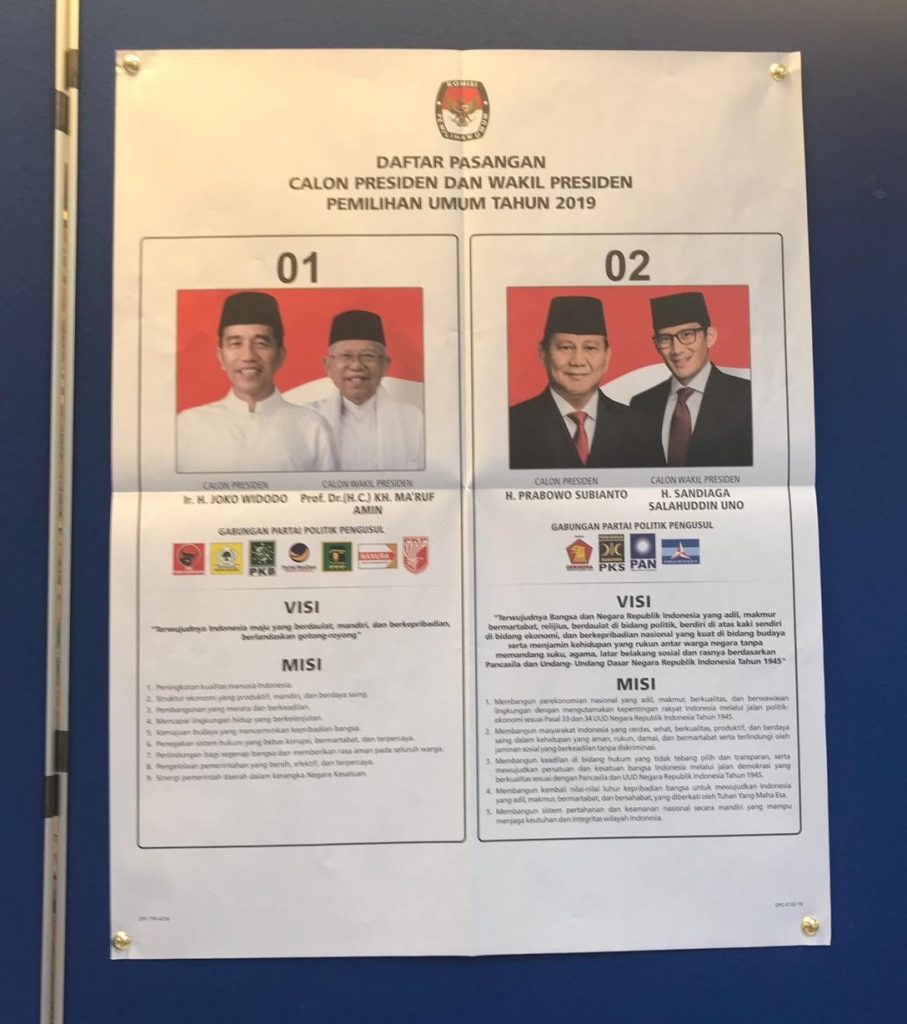

A month later, the election commission, KPU, announced that Jokowi and his vice president, the Islamic cleric, Ma’ruf Amin, had won the presidential election with 55% of votes, compared to Prabowo-Sandiaga’s 45%. The presidential election had involved a total of 16 political parties in the parliament.

The voter turn-out was up to an exceptional 80% in the 2019 election, most likely due to the election day being set up to be a holiday (during weekday), as the Jakarta Globe reported. This marked a historic number in Indonesian election – or indeed in any democratic elections.

The incumbent president’s share of the votes was higher in 2019 than in 2014, when Jokowi won with 53% of the votes against Prabowo with 47%. The voter turn-out had also been lower, though still considerable, 70%. In 2014, Jokowi had been paired up with Jusuf Kalla, the chair of the strong old political party, Golkar.

Jokowi is popular among urban and rural youth. He is considered as a ‘clean’ politician, close to the public and has a reputation of ‘getting things done’ in his previous positions as a mayor of Solo city and governor of the capital, Jakarta. His slogan since 2014 election has been ‘work, work, work!’.

This is in contrast to Prabowo, who is a former military general and whose background is connected to the traditional Indonesian elite, including a connection with Suharto’s family, still considered corrupt.

The election is a show between power and interests (of the elites), as seen from the selection of vice presidential candidates. In the 2019 election Jokowi chose Ma’ruf as his vice-presidential candidate. Given that Ma’ruf is a Muslim cleric, his involvement was expected to attract votes from “more conservative, traditional, and rural voters” and to reduce doubts on the relative weakness of Jokowi’s Islamic background.

Prabowo also had similar strategy, as a known candidate, he chose Sandiaga Uno, a young businessman, hoping to attract youth and urban voters.

Rough campaign

After such a polarizing campaign process, it was unsurprising that there were accusations of massive systemic fraud on the part of Prabowo when Jokowi was pronounced the winner.

Back in 2014, when Prabowo had previously lost, he had resorted to the same accusations. Relying on their competing polling data which showed them the clear winner, Prabowo would dispute the election and challenge the result in the Constitutional Court.

After the official result confirming his loss, Prabowo filed a legal dispute again with the Constitutional Court, alleging that there had been fraud with the election process. Prabowo claimed there had been 17.5 million duplicate names in the voters list, but could not support his claim with more than mostly uncredited evidence and unreliable witnesses. The court ruled against him.

Quite the opposite, the voting system in Indonesia has been greatly improved, as vote tabulation forms of each voting stations are available online, thanks to around 10,000 volunteers to guarantee the openness and fairness of the election.

Despite of complicated and huge election infrastructure, the election was declared democratic and peaceful, confirming also a clear constituency of liberal Muslims who voted for Jokowi.

Indonesia’s politics of usual?

In Indonesia, politics have always been considered ‘bad’ or ‘dirty’. Political parties are associated with money politics, bribery and nepotism among elites. It is true that only rich people can afford politics, including Jokowi.

However, Jokowi is known as a reform-minded leader. Arguably, Jokowi’s presidency features a new governing style of increased openness ─ mostly through social media, which ideally allows citizens to scrutinize every aspects of government policy and comment on them.

While there may be other reasons to Prabowo’s appointment in the Jokowi cabinet, Indonesian political culture has emphasized communitarian ideals before, suggesting that even fierce political rivals should be able to work together for the good of the country.

The opposition parties remain weak in Indonesian politics.

On the other hand, the opposition parties remain weak in Indonesian politics, not only because the parliamentary rules of procedure that are largely outdated and which do not accommodate opposition politics effectively. Quite often, bereft of formal channels, the opposition can only protest government policy via social media.

The direct election system in Indonesia also imbues the president with stronger legitimacy and authority.

For Prabowo, being appointed into cabinet is effectively a greater chance for him and his party, than remaining in opposition. Based on the “national interest” reason, Prabowo is suspected of joining the ruling government in order to improve the future prospects of his Gerindra party and his own likely presidential candidacy yet again in 2024.

So, it is uncertain if Jokowi can offer real reform, or if the election results will simply reinforce Indonesia politics as usual, with patronage and patrimonialism characters over merit, as is advocated by Jokowi.

Ratih Adiputri is a post-doc researcher in political science, University of Jyväskylä.